Accused Witches and Their Suicides in Early Modern Scotland

Share

by Rebekah Stewart

Witchcraft and Suicide: Crimes Against God

In June 1629, Janet Hill was accused and imprisoned for witchcraft in Preston. History of the burgh of Conongate by John Mackay, reports that Hill hung herself, and her remains were “dragged at a horse’s tail to the Gallowelee, and buried under the gallows.” The public disgrace of Hill’s remains was typical of someone who committed suicide. According to Scottish historian and pioneer of witch trial studies, Christina Larner (1933-1983), a death in prison resulted in “the system being cheated of a victim and the community the psychodrama of an execution.” The treatment of Hill’s remains is indicative of standard practices for accused witches who committed suicide, even though she had not had a trial. If someone imprisoned for witchcraft committed suicide, it was viewed as proof of guilt, without a trial of any kind. Moreover, it was thought that the devil himself assisted in the death.

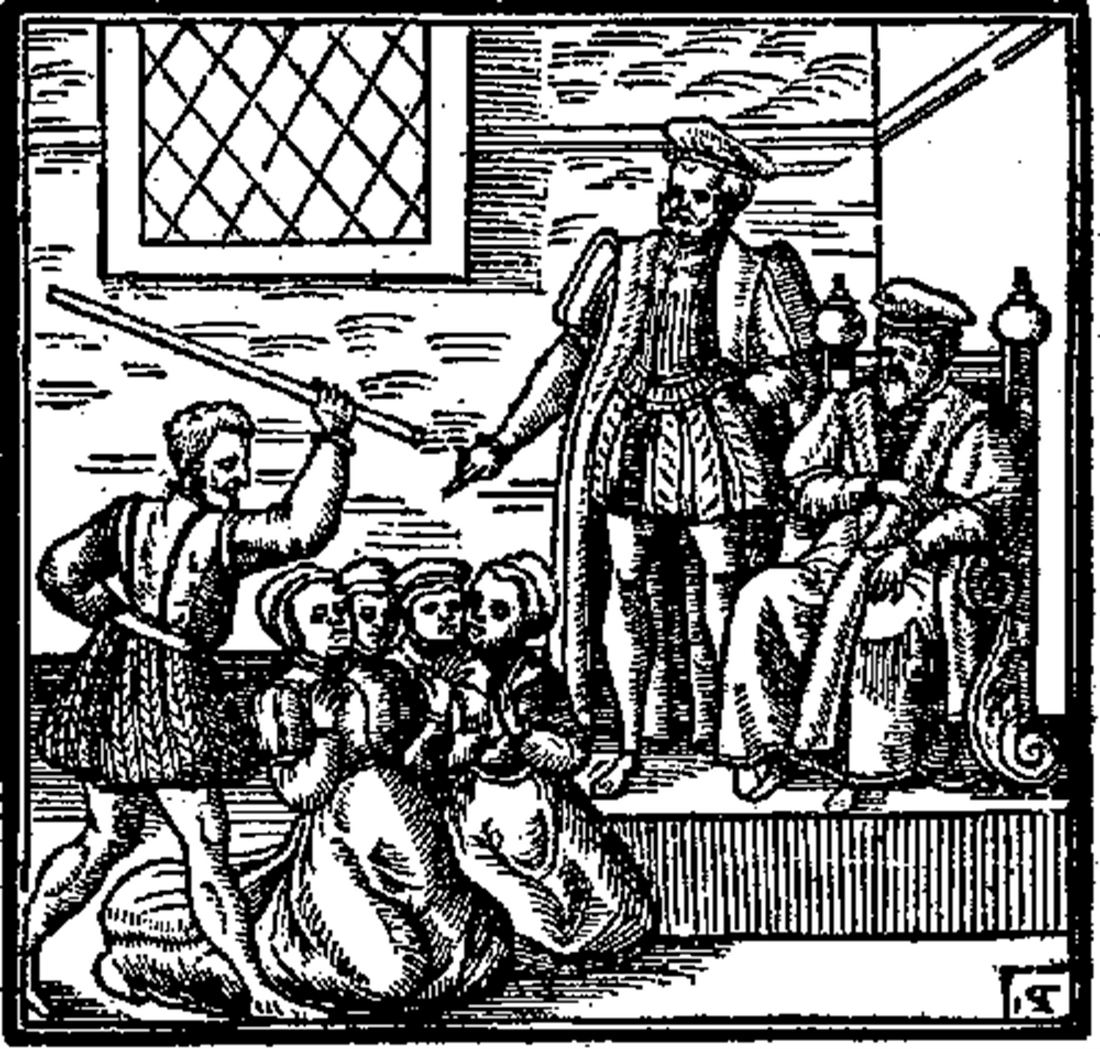

Scotland’s notorious witch trials took place during the Early Modern era, when witch panic was running rampant in communities across the globe. Episodes of witch panic began in the 1400s and continued until the mid-18th century. Religion and law exacerbated belief systems and resulted in significant consequences for Scottish communities. Exodus 22:18, “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live,” was regarded as biblical evidence against witchcraft. During the Scottish trials, the Protestant Reformation of 1560 contributed to witch panic infecting communities. Calvinist theology, spread by John Knox (1514-1572), took a firm hold on Scottish communities and instilled Christian converts with a greater fear of the devil. Within the church, sorcery and witchcraft were considered crimes against God, as well as a civil offense. Likewise, both the church and the state considered the act of self-murder a crime. Beginning in 1563, witchcraft was a capital crime in Scotland, punishable by exile or execution. The Parliament of Scotland, under Mary, Queen of Scots (1542-1587), passed the Scottish Witchcraft Act. Her son, King James VI (1566-1625) of Scotland, and eventually I of England, became the only monarch to be directly involved in a case, during the 1590-91 North Berwick trials, taking an active role in interrogations. Moreover, in 1597, King James politicized and promoted belief in witchcraft by penning "Deamonologie," a book detailing his superstitious beliefs and justifications for the persecution of witches. "Deamonologie" reinforced methods used to identify witches, such as witch pricking and witch swimming. Larner considered King James VI’s book a contributing factor to the increased severity of the Scottish witch trials, as the rate of execution was 2.5% higher than other places in Europe.

Alongside witchcraft history, the study of suicide within a historical context increased, beginning in the 1980s, and became a distinct niche of study. While the history of suicide is more complex and difficult to determine a distinct starting point, recent scholars have published works that aim to gain a better understanding of how suicide demonstrates individual perspectives on events in history. Examining instances of suicide gives historians valuable insight into the minds of people living through significant events and turning points in history. Witchcraft and suicide were thought to have a direct relationship with the devil. Suspected witches allegedly entered a pact with the devil in exchange for magic powers to conduct the devil's bidding. The act of self-murder was also thought to be influenced by or caused by calling upon help from the devil. The word “suicide” was not coined until the 1630s and not widely used until the 1700s. As shown in the Scottish trials, the two crimes against God collided when accused witches chose to take control over their own lives when facing a situation that sought to strip them of their agency.

Woodcut from Newes from Scotland (1591) pamphlet depicting King James VI participating in interrogations in the North Berwick Trials.

Punishments for Pacts with the Devil: Torture, Execution, and Desecration

Punishment for witchcraft varied depending on the location of the accusation and subsequent trial. In Scotland, the most common treatment for someone found guilty of witchcraft was being publicly strangled, and their remains burnt at the stake. It’s estimated around 3,800 accusations took place in Scotland. Women were disproportionally targeted for suspected witchcraft, especially older women and women known for holistic healing abilities. Those found guilty and executed for witchcraft often had their remains publicly disgraced and were denied Christian burial rites. The surviving family of an executed person may also be billed for costs incurred for the death. Scottish courts liberally used various torture methods to extract confessions from accused defendants, despite no existing legal precedent to do so.

Scottish interrogators were especially brutal in their torture methods against suspected witches. For example, in 1591, Geillis Duncan had her thumbs sinched in a contraption called a thumbscrew. Margaret Barclay and Isobell Crawford had heavy weights placed on their legs to extract confessions. In 1632, Janet Love was stabbed with needles, hit with bowstrings, and wedges driven into her shins. In 1652, a group of 6 accused were hung by their thumbs while candles were placed under their feet, in their mouths, and on their heads. Sleep deprivation was a common method used to force confessions from delirium. The method of witch pricking was used to identify a witch, where suspected witches would be pricked with needles in various parts of the body in search of the “devil’s mark,” a place that was free of pain and would not bleed. Although less common in Scotland, witch swimming was presumed to prove the guilt or innocence of an accused person. If one did not drown in the water, it was assumed that the devil would help to keep them floating. However, if the person drowned, they were thought to be innocent.

Similar to how those found guilty of witchcraft were treated posthumously, a person who committed suicide would have been treated differently than someone who died of non-self-inflicted causes. In terms of religious consequences, persons who committed suicide were denied Christian burial rites and would be laid to rest outside consecrated grounds. As for civil offenses, the families of the person who committed suicide would bear the brunt of the punishment. A suicide found to be committed due to insanity may be pardoned, but if the deceased were not found to be considered mentally ill, punishment was more likely. The surviving family of the deceased may be subject to paying fines to avoid their loved one’s corpse being publicly displayed or mutilated. In addition, the estate of the deceased may be seized by authorities, leaving the surviving family without a home or property. As illustrated by the stories of those who were accused witches who committed suicide, the punishments for each respective crime were combined in a gruesome treatment of human remains.

Woodcut showing suspected witches enduring torture.

Public Execution vs. Suicide: Choosing Death to Reclaim Agency

On the accused and imprisoned in Scotland, Larner noted that “many committed suicide. It is not always clear which deaths were through neglect, which through torture or ill-treatment, and which were suicide.” Those who took their lives, such as Janet Hill mentioned at the outset, experienced similar treatments in death. According to George Black’s Calendar of Witchcraft in Scotland, the earliest suicide of a suspected witch was Issobell Monteith, who hung herself in prison in 1596. Monteith’s case is the first suicide that records exist from, not necessarily the first. A lack of surviving records of Scotland’s trials is a known hindrance to researchers. According to the record, like the remains of Hill, Monteith’s remains were dragged by a cart through the town before her burial.

The next recorded suicide occurred in 1618, when John Stewart, Isobel Inch, Margaret Barclay, and Isobel Crawford were caught up in a witch trial in Irvine. Stewart and Inch were accused of witchcraft alongside Margaret Barclay and Isobel Crawford. In Sir Walter Scott’s retelling of the case, Stewart was the first apprehended and reportedly, undergoing extreme torture, implicated Barclay as being the leader of the local witch coven, cursing a causing a ship to sink, and devil worship. According to the trial manuscript, Stewart was discovered by officers, who found him strangled and hung by the crux of the door with a string of hemp. It’s impossible to say if Stewart was overcome with guilt by his part of the trial process, or took his life into his own hands to escape a public death. Inch was reported to have died five days after jumping from the belfry in an escape attempt. Just as Stewart’s motives are unknown, whether Inch was trying to escape with her life, or end her life to escape further torture, trial, and public death is impossible to know.

In 1697, during a series of trials in Paisley, John Reid committed suicide while in prison for suspected witchcraft. Esquire Kirkpatrick Sharpe recorded that Ried “strangled himself in prison, or, as the report went, was strangled by the devil.” Reid’s death further illustrates how the public viewed the suicide of an accused witch during the time. It was thought Reid must have had the devil’s aid in his death because of his accused status. Similarly, in 1677, in Haddington, an accused witch named Margaret Kirkwood, hung herself in prison. According to the manuscripts of John Fountainhall, “some say she was so strangled by the devil and witches.” Reid and Kirkwood’s deaths illustrate a pattern of public thought surrounding suicide committed by accused witches. Even in death, accused people had little chance of exoneration in the eyes of the public. In fact, their death by suicide acted as proof they were working with the devil and confirmed their guilt of witchcraft.

Isabel Davidson’s case is particularly interesting because of the way she chose to take her own life. According to Black’s Calendar of Cases of Witchcraft in Scotland, at Belhelvie in 1676, Davidson drowned herself after being charged “with using charms for the cure of diseases.” Davidson’s case is fascinating for two reasons: the chosen method of death and the evidence used to arrest her. Davidson’s use of water in her death leaves room to speculate that she may have been aware that drowning would be a way to exonerate herself. She denied involvement with witches' Sabbath activities, admitted to healing with charmer practices, and inferring information about patients by using astrological signs, which, according to Davidson, she read about in books. Davidson was referred to the presbytery to be examined and requested to bring her book to the next meeting the following month. However, she threw herself in the water and drowned before the next meeting took place. Since Davidson was reading astrology books, it gives reason to believe she may have been familiar with Daemonolgie, and thus be aware of witch swimming as a proof of innocence by drowning.

Instances of witch trials decreased steadily after the 1660s until the Witchcraft Act was repealed in 1736. Scholars attribute the decline of witchcraft trials to waning belief in supernatural ideologies amongst elites, scholars, and common folk, in addition to growing skepticism of the reality of witchcraft being a crime. The decline of religious and supernatural belief systems alone was insufficient to curb witch trials. However, it aided the eventual repeal of the law, which finally put a stop to trials completely. Looking at the known persons who took their own lives because of the accusations directed at them sheds light on a dark period in Scottish history. Hill and Monteith’s cases exemplify how the remains of suspected witches who committed suicide were treated. Ried, Kirkwood, and Stewart’s deaths show that suicide in prison, especially when accused of witchcraft, was strongly associated with the devil’s help in death. Davidson’s story is an interesting case of an attempt to prove her innocence through her death. The stories of Hill, Monteith, Ried, Kirkwood, Stewart, and Davidson exhibit the brutality of Scotland’s witch trials and illustrate how some reclaimed agency over their lives by choosing death.

An illustration from The History of Witches and Wizards (1720), depicting witches offering wax dolls to the Devil as part of a ritual.

Rebekah Stewart is an independent scholar and photographer. Her projects can be found on her Substack. She graduated summa cum laude from Washburn University, where she earned her bachelor’s degree in history. The last year of her studies focused on Scottish history, particularly the Scottish witch trials. When she isn’t researching, she’s working out at the gym, taking photos in cemeteries, checking novels out from the library. She lives in Kansas with her fiancé and their cat.