The Tudor Curse by Tim Hasker-Sarchet

Share

A Dynasty is Born

In August 1485, Henry Tudor emerged from the chaos of civil conflict to seize the English crown at the Battle of Bosworth. His triumph over Richard III inaugurated a dynasty that would rule for over a century and whose greatest anxiety, from its inception to its end, was the question of succession. Though his claim was tenuous—descended through the Beaufort line, legitimised by royal decree but barred by statute from inheriting the throne—Henry VII consolidated his position through a marriage of deep political symbolism. By wedding Elizabeth of York, the daughter of Edward IV, he sought not only to fuse the warring houses of Lancaster and York but to silence residual Yorkist claims. Nevertheless, dynastic insecurity continued to haunt the early Tudor regime. Henry VII's early reign was punctuated by uprisings and pretenders, most notably Lambert Simnel and Perkin Warbeck, each of whom garnered significant foreign and domestic support. Simnel, claiming to be the Earl of Warwick, was crowned in Dublin and led an invading army into England. Warbeck, claiming to be Richard, Duke of York, the younger of the Princes in the Tower, received recognition from Margaret of Burgundy and the court of James IV of Scotland. Though both threats were ultimately suppressed, their emergence underlined how conditional and vulnerable Tudor authority remained in the eyes of many. Dynastic security seemed briefly assured with the birth of Prince Arthur in 1486, followed by a series of children, including Margaret and Henry. Arthur was married in 1501 to Catherine of Aragon, daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, in a union meant to cement Anglo-Spanish alliance and affirm Tudor legitimacy. His death in 1502, aged fifteen, was a severe blow. With Elizabeth of York dying in childbirth the following year and other children not surviving infancy, Henry VII's final years were marked by dynastic fragility. The hopes of the dynasty now rested on the second son, Henry, Duke of York, whose life had not been shaped with kingship in mind.

Henry VII

Henry VII

King's Great Matter

When Henry VIII ascended the throne in 1509, he inherited not only a crown but the dynastic uncertainties of his father. Though young and energetic, he was acutely aware of the dangers of a contested succession. His early marriage to Catherine of Aragon—his brother's widow—was both an assertion of continuity and a political necessity. Their union, however, produced only one surviving child, Mary, born in 1516. A series of miscarriages and infant deaths eroded hopes of a male heir. Henry, convinced that the failure was divine punishment for marrying his brother's widow, sought an annulment from Pope Clement VII. The Pope's refusal, complicated by Catherine's ties to the Spanish Habsburgs and the imperial occupation of Rome, led to a fundamental rupture. The so-called "King's Great Matter" catalysed the English Reformation. In 1533, Henry married Anne Boleyn, and through parliamentary statute and clerical pressure, declared himself Supreme Head of the Church of England. This break from Rome was not driven purely by theological conviction but by the desire to control the succession. Anne bore him a daughter, Elizabeth, in 1533, but subsequent pregnancies ended in miscarriage or stillbirth. Anne's failure to provide a male heir, coupled with court faction and Henry's disillusionment, led to her arrest and execution in 1536. Her downfall paved the way for Jane Seymour, who bore Henry a long-awaited son, Edward, in 1537. Jane died shortly after childbirth, but her memory was preserved as the mother of the Tudor future. The remainder of Henry's reign was marked by continued manipulation of the succession. His marriage to Anne of Cleves in 1540 ended in annulment, while his fifth wife, Catherine Howard, was executed for adultery. His sixth and final wife, Catherine Parr, survived him but bore no children. In a series of Succession Acts passed by Parliament, Henry altered the line of inheritance, declaring both Mary and Elizabeth illegitimate at different times, only to reinstate them later, albeit with ambiguity. His 1544 Act of Succession and final will named Edward as his heir, followed by Mary, then Elizabeth. Yet legitimacy, in Tudor terms, was increasingly shaped by statute rather than lineage alone. Edward VI became king in 1547, aged nine. His minority necessitated a regency, first under the Duke of Somerset and later the Duke of Northumberland. Edward, precocious and staunchly Protestant, continued and deepened the religious reforms of his father. His fragile health, however, made the succession once again a matter of urgent concern. Fearing the Catholic restoration that Mary would bring, Edward and his advisors devised a new succession plan. In his "Devise for the Succession," he excluded both his half-sisters and named Lady Jane Grey, granddaughter of Henry VII's sister Mary, as his heir. Jane, married to Northumberland's son, was proclaimed queen upon Edward's death in July 1553.

Henry VIII, Jane Seymour, and Edward VI

Henry VIII, Jane Seymour, and Edward VI

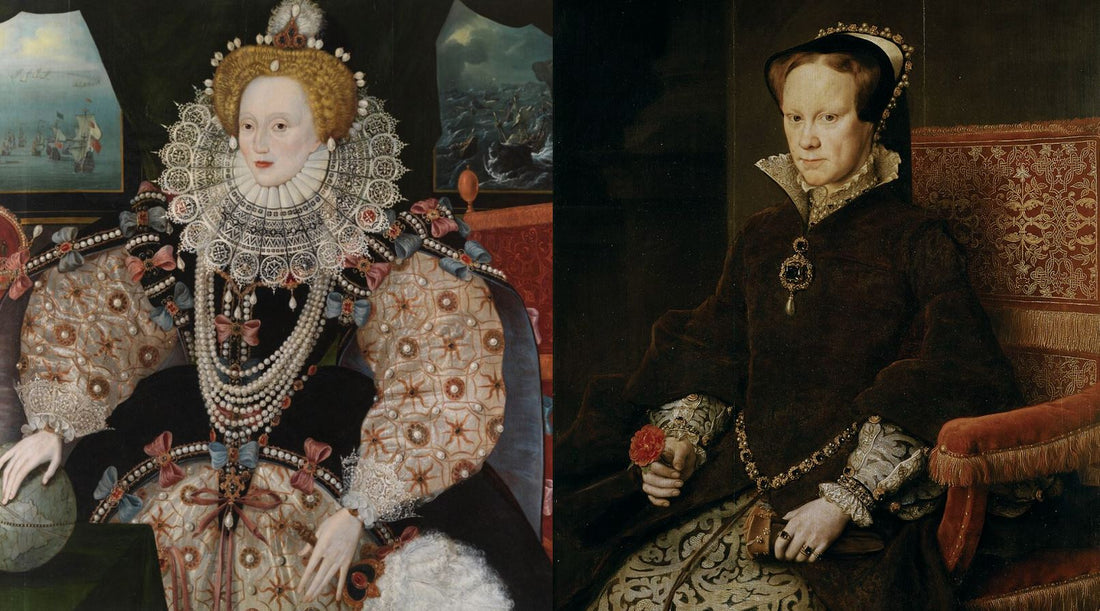

Two Sisters, One Crown

Her reign lasted only nine days. Mary, who enjoyed greater popular support and a stronger claim by birth, raised an army and entered London to cheers. Jane was deposed and eventually executed. Mary's accession marked the first time England was ruled by a queen regnant. Her reign, defined by a return to Catholicism and a politically fraught marriage to Philip II of Spain, aimed to reverse the Reformation and secure a Catholic succession. Yet Mary's pregnancies proved illusory, and no child was born. Her reign, though it restored papal authority and persecuted Protestants, did not produce the long-term Catholic future she had envisioned. Upon her death in 1558, the crown passed to Elizabeth. Elizabeth I, daughter of Anne Boleyn, assumed the throne amidst religious division and political uncertainty. Though declared illegitimate by her father's earlier legislation, she was accepted without significant resistance. Her reign would become one of the most celebrated in English history, yet it remained shadowed by the unresolved issue of succession. Elizabeth refused to marry, citing a combination of political prudence, personal conviction, and the memory of her mother's downfall. The notion of a "Virgin Queen" became a cornerstone of her public image, but it ensured that no heir would be born of her body. Throughout her reign, Parliament and advisors urged Elizabeth to settle the succession. Various suitors were proposed—including foreign princes and English nobles—but none were accepted. The danger of naming a successor too soon was not lost on Elizabeth; to do so risked inviting factionalism or rebellion. The presence of Mary, Queen of Scots, a Catholic with a strong hereditary claim, posed a persistent threat. Mary's imprisonment in England and eventual execution in 1587 removed a rival but did not resolve the question. Elizabeth's refusal to clarify the future left her ministers to navigate a delicate political balance. By the late 1590s, attention turned to James VI of Scotland, son of Mary, Queen of Scots, and great-grandson of Henry VII. Protestant and experienced in kingship, James emerged as the preferred candidate among Elizabeth's advisors, particularly Robert Cecil. Though Elizabeth never formally named him her heir, diplomatic correspondence and political planning prepared the ground. When she died in March 1603, James was proclaimed king without opposition, marking the end of the Tudor line and the beginning of the Stuart dynasty. The Tudors, for all their consolidation of royal authority and national identity, never resolved the fundamental instability of succession. Their century of rule was characterised not by dynastic abundance but by a persistent scarcity of heirs, compounded by religious upheaval and legal ambiguity. Each monarch, in turn, inherited not only a crown but a crisis. That the transition to James I occurred peacefully was less the result of Tudor planning than of pragmatic statesmanship in the final years of Elizabeth's reign. The succession question, which had defined and haunted five monarchs, was settled at last—but not by Tudor hands.

Elizabeth I and Mary I

Elizabeth I and Mary I

About the Author

Tim has had a lifelong passion for history which started when his father bought him a 'Kings and Queens of England' book from Dover Castle in the early 90s. This love for history grew during his childhood with an almost obsessional interest for all things Ancient Egypt. He has a masters degree in history and specialises in 17th century history. He has written for several publications and museum reviews, as well as working as a researcher on several heritage projects and as a presenter on a documentary about the First World War. He lives in Birmingham with his husband and their two cats and can usually be found in one of the bars of Stirchley.