Historians and the Immunity Debate: Revisiting Yellow Fever in New Orleans

Share

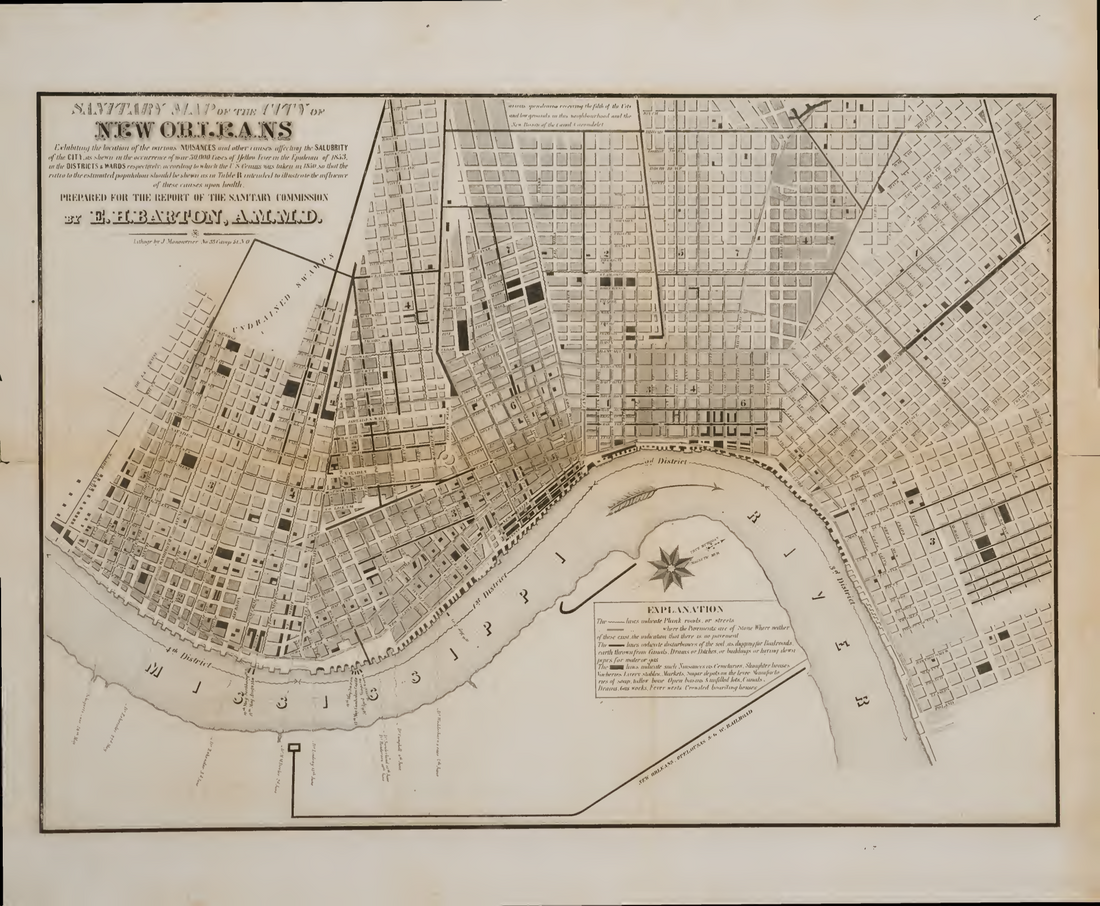

In the nineteenth century, New Orleans faced significant challenges due to yellow fever, a viral haemorrhagic fever transmitted by mosquitoes. But as yellow fever epidemics increased in frequency and ferocity, immunity became vital as it impacted people’s lives and prospects.

While white elites claimed Black people had an inherent immunity to yellow fever as a justification for permanent racial slavery, some modern historians believe in this outdated claim. For example, Kenneth Kiple, of Bowling Green State University, and historian Virginia Kiple believe this claim and argue that a consensus existed among the historical observers that Black people were inherently immune to the disease. They cite eighteenth and nineteenth-century medical literature, which discussed Black immunity as an accepted fact.

However, a closer examination of these debates reveals a more complex picture where the idea of racial immunity was far from universally accepted. During the eighteenth century, many physicians asserted that Black people never contracted yellow fever. John Lining (1748), an influential observer of the disease, claimed he had never encountered a case among Black patients, attributing their apparent resistance to a unique physiological constitution. His observations gained traction and were echoed by prominent physicians such as Benjamin Rush (1796) and Philip Tidyman (1826). In believing in Black immunity, Rush encouraged Black residents to remain in cities during outbreaks to assist in relief efforts. Tidyman similarly promoted the idea that Black labourers could endure extreme heat with minimal suffering, reinforcing the notion that they were biologically different and suited to hard labour, thus justifying the need for Black slave labour.

By the mid-nineteenth century, however, medical discourse on Black immunity began to shift. Physicians rarely claimed Black individuals were entirely immune, but that they experienced milder symptoms. Samuel Cartwright (1853), an influential Southern physician, proclaimed that Black people were ‘perfect non-conductors of yellow fever,’ a sentiment that found widespread support among Southern medical professionals. Drs. Fassit (1855) and Josiah Nott (1846) were among his most vocal allies.

Fassit documented an outbreak at Oaklawn, where only six of the 130 enslaved individuals who fell ill ultimately died. He used these figures to argue that yellow fever was far less dangerous to Black individuals than to white patients. Nott reinforced this belief, asserting that while Black people could contract yellow fever, their symptoms were less severe and their survival rates higher.

The acceptance of racial immunity extended beyond the medical community into broader society. Historians Kiple and Brian Higgins argue that 'Black immunity' was deeply ingrained in the public consciousness. Katherine Olivarius of Stanford University suggested that this belief was rooted in existing racial ideologies that sought to justify Black labour under extreme conditions. This can be seen in newspaper articles of the time, claiming that Black children were fed ‘fatal’ quantities of alcohol and coffee as proof of their different constitutions and inherent immunity to yellow fever.

Such arguments shaped economic decisions, as plantation owners were reassured that their enslaved workforce would be unaffected by outbreaks. In a striking example in 1856, William Dewees sued a fellow planter for selling him an enslaved person who soon died of yellow fever, asserting that the individual had been misrepresented as ‘immune’ to the disease. While this lawsuit contradicts the idea of Black immunity, it underscores how deeply the belief had influenced economic and social practices.

Despite the widespread promotion of 'Black immunity', many medical professionals rejected this theory. Some argued that Black individuals were not naturally immune but rather had acquired immunity through repeated exposure to disease. James Johnson (1818) suggested that Africans might resist yellow fever because of cultural practices such as oiling their skin. While John Eberle (1821) dismissed this reasoning, he supported the idea that Black individuals who survived previous outbreaks developed resistance through acquired immunity rather than inherent racial traits. Similarly, William Holcombe (1879) rejected Cartwright’s claims, calling them ‘baseless as the fabric of a vision.’ Even early advocates of racial immunity, including Rush and Fassit, reconsidered their position after observing severe yellow fever cases among Black patients.

These ongoing debates highlight that no clear consensus existed among historical observers regarding Black immunity to yellow fever. Historians who argue otherwise misinterpret the shifting nature of the medical literature. The transition from theories of inherent racial immunity to acquired immunity has often been overlooked, leading scholars to conflate the two concepts. Acknowledging the medical debates of the time, we gain a more nuanced understanding of how race and public health intersected in nineteenth-century New Orleans. Recognising these complexities is essential to dismantling outdated assumptions and portraying a more accurate history of yellow fever and 'racial immunity'.

Eleanor Smith is a History of Medicine MA graduate from Newcastle University. Her dissertation studied the medical influence on the environmental design of the French Riviera’s health resorts in the late nineteenth century, which won her the Cowen Memorial Scholarship Prize. She has recently written articles for EPOCH History Magazine on Rembrandt and anatomy. She has also spoken at the Museum Association Conference and the Jungend Konferenz 2024 about the power of young people in museums and is currently researching youth participation and engagement in museums and how museums can develop when considering a youth voice.