Murder on the North London Railway

Share

The Crime

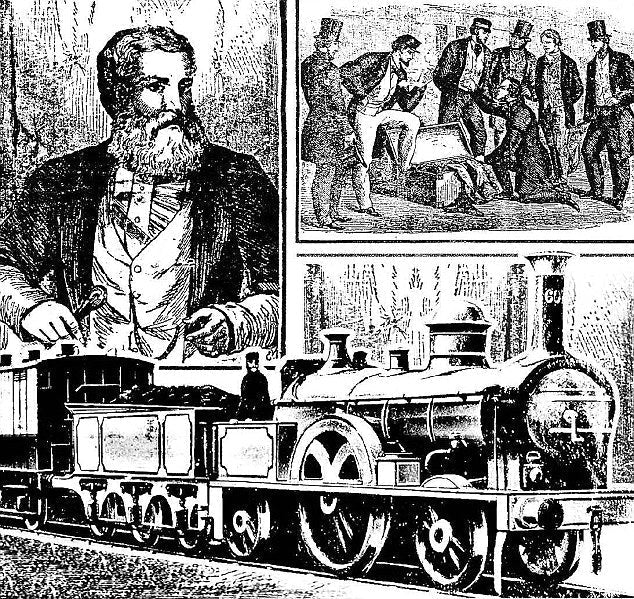

On Monday, 14th November 1864, a German tailor by the name of Franz Muller was executed outside Newgate Prison to a crowd of around 50,000 spectators. And so ended a murder case which had gripped the nation in a media frenzy since the body of Thomas Briggs was discovered in the July of the same year. In addition to being one of the last public executions, this case was also a first – that is, the first murder to happen on the railways.

On Saturday, 9th July 1864, the 9.50pm train from Fenchurch Street on the North London Railway arrived at Hackney at 10.11pm. The guard was called to a first-class carriage by two bank clerks who had entered it and discovered blood all over the cushions of the compartment. A black beaver hat, a stick and a bag were also discovered. Upon arrival at Chalk Farm station, the carriage was detached and sent to Bow for examination and the discovered items handed in to the Metropolitan police.

Meanwhile, another train travelling in the opposite direction discovered the body of an unconscious, severely injured man by the tracks – the victim, and owner of the possessions found in the blood-covered compartment, was identified as Thomas Briggs, a 69-year-old city bank chief clerk. He died the following night from his injuries. The Government, the North London Railway and Briggs’ employers each offered £100 rewards for information leading to the capture of his killer – a jeweler by the name of John Death subsequently come forward and gave a description of a German man who had come to his shop on 11th July and exchanged a gold chain (later identified as belonging to Thomas Briggs).

A week later, a cabman named Matthews informed the police that he had found a box in his home with the name ‘Death’ on it, and the box had been given to his children by a young German named Franz Muller. Muller was, at the time, engaged to Matthews' eldest and was further identified by Death as the man who exchanged the gold chain. However, the investigation found that Muller had already sailed for New York on 15th July.

The police were able to beat Muller to New York. When he was arrested on arrival, he was searched and found in possession of Briggs’ watch. Following an extradition process, Muller was transported back to England for trial. The defence argued that the evidence was circumstantial, producing an alibi for Muller and Muller himself consistently protested his innocence. But Muller, who had had a previous conviction for theft, was found guilty of murder by a jury and executed in front of large crowds at Newgate Prison.

The Press

The murder investigation and trial whipped up a frenzy in the media. The response and public reaction tell us a lot about how Victorian society viewed violent crime and the emergence of 'stranger danger'. The initial reaction in the press viewed the murder as an attack on civilised society. For example, The Daily Telegraph's representation of the crime on 12th July 1864 stated: “Is there not in this incident something which is personal to tens of thousands of our citizens? The crime suggests a danger from which no one can flatter himself that he is absolutely exempt". In these words, the paper is positioning the perpetrator as outside of civilised society, and the crime as an attack on society itself.

In addition to the crime being painted as an attack on respectable society, the press’ immediate reaction to the crime taking place on a train demonstrates an anxiety concerning the modernity that railways presented. The railway was the driving force of British modernity. However, for many, it symbolised everything that was going wrong in society – the murder of Thomas Briggs was just further evidence of the depravity it was causing.

The papers also used the case as an opportunity to strike political attacks. For example, the liberal Morning Star’s criticism of the investigation highlights the discontent there was surrounding the effectiveness of the police and wider domestic political issues. Moreover, Muller’s German nationality was repeatedly raised by the papers to exaggerate the threat of foreigners. What is also interesting is that the papers suggest that the murder rates in London were as bad as they were in various other countries renowned for their criminality. Whereas, in fact, by the mid to late nineteenth century, the homicide rate was significantly lower in England than it was in Italy, for example. The xenophobic nature of the trial by public opinion, which the papers had subjected Muller to since he was identified, led the German Legal Protection Society to question the impartiality of the jury.

The xenophobia of the Muller case coverage reflected a broader change in attitudes towards crime that was developing during the mid-nineteenth century. Traditionally, crime had been viewed as resulting from universal sinfulness and therefore, something which anyone could succumb to. This belief in the ‘everyman criminal’ resonated with religious sentiments, and publications relating to murder and executions were formulaic to reinforce religious conformity and social order. They would detail how the criminal was an ordinary person, who fell from grace due to unnatural behaviour or influence from the Devil – there would always be a confession and a begging for mercy from God before execution. However, by the time of the Muller case, there was an emerging theme of ‘stranger danger’ where criminals were increasingly being presented as ‘monsters’ who were subhuman and not part of civilised society. The development of ‘polite society’ found the universal nature of the ‘everyman criminal’ distasteful, and this can be seen in how Muller was portrayed as a foreign monster. Moreover, the coverage of murder cases, especially with Muller, was increasingly interested in the grisly details, signifying a shift away from moral messaging to crime reporting as a method of entertainment. A trend that would continue and is arguably still prevalent today, as seen with the popularity of true crime.

Execution and Legacy

Franz Muller was executed to an almost riotous crowd of 50,000 spectators, whose drunken and criminal behaviour shocked the establishment to its core. For many, they were a horde made up of the criminal underclass, of which Muller was a member. Even newspapers such as The Times, who were highly supportive of public executions, began to question its ability to moralise the lower classes.

A criminal underclass is a constant theme throughout the Muller case – the image of a respectable gentleman being mugged and murdered in a first-class carriage by a foreign, unrepentant criminal played perfectly into the growing belief in the 'monster murderer'. This was a consequence of the changing nature of urban life – social reforms and a shift in values meant that the belief in universal sinfulness (prevalent in eighteenth-century England) was becoming less relevant to society. Criminals, therefore, weren’t ordinary people who had fallen, as they were represented to be in the eighteenth century, but were separate from society – the monster criminals; a belief which contradicts the well-established fact that you are most likely to be murdered by somebody of the same social and ethnic makeup as yourself.

Nevertheless, reporting on the execution of Franz Muller emphasised a deep-rooted social concern in the growth of a criminal underclass.

"Under the very feet of the gallows, with the strangled corpse still warm and suspended and swaying before their eyes, gangs of plundering ruffians – the bloated, brutalized and felon-face outcasts of a superficial civilization…Therefore, for the protection of human life, and in the interest of that civilization outraged and disgraced by such scenes as that witnessed in front of Newgate on the morning of Monday last, it is desirable that other punishment for murder should be devised than that public strangulation which always disgusts and depraves”

- Reynolds' Newspaper, 20th November 1864

This excerpt demonstrates that to the press, whose target audience were the middle and upper classes, their way of life was under threat by this criminal underclass who were being encouraged rather than deterred by the public execution of Franz Muller. These concerns would form part of the argument for the abolition of public executions, which would happen four years later in 1864.

The Muller case both excited and horrified polite society. This appears to be the great contradiction of the nineteenth century that, on the one hand, you could argue a civilising process was happening, due to such social reforms as the decline of the bloody code, abolition of slavery and the eventual ban on public executions. But, on the other hand, you have the perpetuating fascination with murder through continued readership of broadsides, crime novels, gruesome souvenirs, plays and exhibitions such as Madame Tussauds' Chamber of Horrors.

Fascination with murder and violence became an increasingly private affair, far removed from the public display of executions of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Rather, this fascination expressed itself through novels, plays and exhibitions. Does this mean, however, that England was less violent or had polite society convinced itself that the civilising process had been a success, and the populace had outgrown their violent tendencies? I would argue that the emergence of the monster murderer as a replacement for the everyman murderer demonstrates that mid-late nineteenth-century England was in denial about the reality of violence in their society in comparison to their eighteenth-century ancestors, for whom violence was not fantasy but everyday life.

The case of Franz Muller is fascinating and complex – it holds an important place in the history of nineteenth-century England and can tell us a lot about how Victorians not only viewed murder but their society more broadly. It is uniquely placed as being not only the first murder to happen on a train, but it is also the beginning of the end for public executions. It shines a light on a society that was uncomfortable with the pace of modernity and fearful of a criminal underclass.

The Muller case further demonstrates how murder was becoming a private matter, civilised society had moved from the concept of the everyman criminal to the monster murderer which Muller represented. As the century moved on, the concept that criminals were abnormal and outside of ordinary society would become further entrenched by infamous murderers such as Jack the Ripper.

Tim Hasker-Sarchet holds a masters degree in history and has written for several publications and museum reviews. Tim has worked as a researcher on several heritage projects and as a presenter on a documentary about the First World War. He has had a lifelong passion for history, which started when his father bought him a 'Kings and Queens of England' book from Dover Castle in the early 90s. This love for history grew during his childhood with an almost obsessive interest in all things Ancient Egypt. Tim lives in Birmingham with his husband and their two cats and can usually be found in one of the bars of Stirchley.